I was speaking to a friend the other day, and they mentioned that they had no idea what I was up to these days. I found it strange, how could they not know what I was up to?

Then I realized, I hadn’t really told anyone what I’ve been up to. So, I’m going to remedy that today:

The past couple years have been pretty busy for me. That drive to keep busy came out of a less than ideal situation. I was pretty lonely at Georgia Tech. There weren’t many people who understood my religious background or who were interested in dreaming up big visions with me. So I took all that energy and put it towards doing cool stuff.

I started off as a physics major, which turned into a minor as I realized that physics is really hard. Yet, some of the few classes I genuinely enjoyed in college were in the physics department, among them: Thermodynamics, Quantum Mechanics I, and the Physics of Small Systems. My first year, I also started reaching out to a random professor every week, a tradition that ended up being one of my highlights of college. I managed to get coffee with dozens of really interesting people from every department allowing me to explore a bunch of different fields in a very short amount of time.

My second year, I switched my major to Biomedical Engineering. With that switch, my class attendance dropped precipitously as I thoroughly hated most of the classes. In fact, I only enjoyed a single class throughout my entire time in BME. By my third year, I only went to classes that graded participation, and even those I rarely attended. For project-based classes, I was the worst teammate you could ask for. My only goal was to keep my scholarship which required a GPA of 3.3, and that is what I did. I mostly got Cs and Bs, with a couple Ds sprinkled in. Yet, I found a hack:

Whenever you do academic research, you can get your research mentor to grade your research. And that letter grade can influence your official GPA. So to counteract my course grades, I did a ton of research allowing me to keep my GPA above a 3.3. I started off doing research in data science, working on removing bias from the graduate admissions teams in a couple departments at GT. I also worked on making a digital Talmud, which eventually connected me with some of the great people at Sefaria.

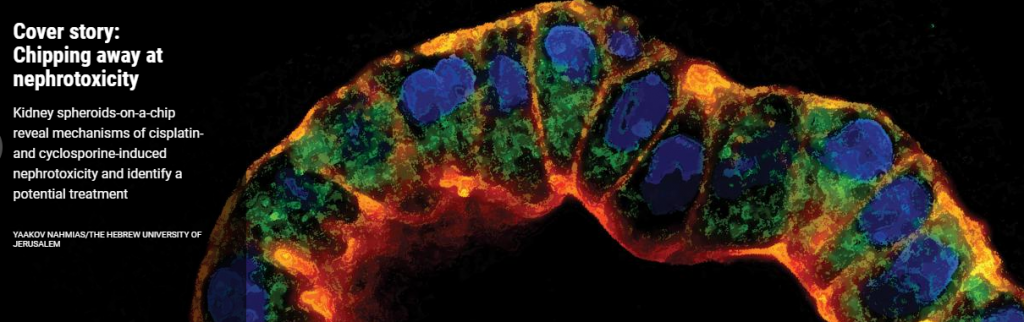

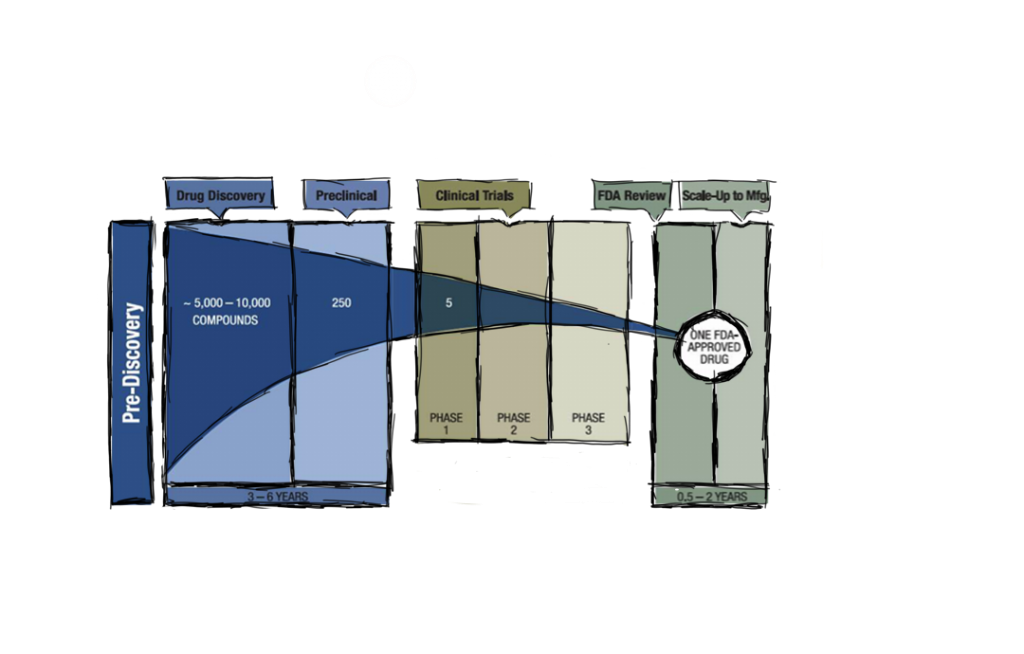

In my second year, I moved from data science to bioinformatics. That is where I spent the vast majority of my time and got some papers published. I worked on cell-based meat, tissue-on-a-chip technologies, and population genomics. I worked in 2 or 3 labs at the same time to increase the number of hours I was doing research. It was fascinating, but I saw that the field was seriously underdeveloped. In fact, it was so underdeveloped that they let me (a 21 year old) make bioinformatic pipelines because no one else was doing it. So, as I was getting ready to graduate, I decided to take a break from bioinformatics to start a company.

My thinking was that I eventually want to make a company that can help people engineer and program cells, yet in order to make that company, I need a lot of investment and advancement in the field. So in the meantime, I will prove myself with another start-up and then make my way back over the next two decades.

Before I started the company, I actually tried to apply to a bunch of internships. I got rejected from all of them. So with no better options, I decided to take the leap and start a company during my last semester at GT.

That is what I am up to now: building a startup called 402. I raised some VC money (which was a whole journey in itself) and now we are a team of about 9 people working on making the internet a better place. I am going to leave it pretty vague for now, but reach out if you are interested and I can tell you a bit more. I am raising our next round in July to grow the team and expand the product, so I will release more details publicly then.

It has been pretty amazing to build a company. It is extremely stressful, but I find it rewarding and challenging. I get to work every day alongside really cool people on important things. It is the first time in my life where I feel that the work I am putting in has the chance to directly impact others’ lives. I take that responsibility very seriously and want to prove to myself, my investors, and my family that when I put my mind to something, I can do big things.

Yet, a feeling of disbelief always looms over me. What place does a 22 year old have hiring people older than him? What right do I have to be managing the amount of money that I am? I seemingly haven’t worked hard enough for this opportunity, yet here I am. I have to occasionally pinch myself to bring my attention back to reality because my head can often wander down this path of self-doubt. This is not even considering the ever present threat of failure. People have put their faith in me. Our investors trusted me with their money. Our employees trusted me with their careers. I plan on succeeding, but what happens if I don’t?

Luckily, I am a pretty resilient guy and these thoughts don’t bother me too much. Sometimes they keep me up at night, but more often than not they keep pushing me forward. I have come to terms with the possibility of failure. I have built a high tolerance of risk, and am OK with failing. It doesn’t define who I am, and I have surrounded myself with people who are aware of the risks.

On top of all that, I am making Aliyah in July. I am looking forward to starting my life in Israel. I haven’t been surrounded by people my own age for quite a while, so I am hoping to improve my social life there. Between now and July, I am traveling around. I am going to be in Israel, Europe, NY/Miami, Atlanta, and Kenya. I plan on doing a lot of hiking, rock climbing, and socializing. I am particularly excited about hiking Kilimanjaro in June.

I have big plans for the future. I want to be a part of the biological revolution that is coming over the next two decades. Advancements like nanopore sequencing, CRISPR, AlphaFold, and IPSCs have enabled us to learn so much about what is possible. Cells can do so much more than we thought. They are a mechanism that fights entropy like no other. While everything else in life degrades over time, cells grow and collaborate using amazingly clever tricks to fight an environment trying to kill them.

I fully believe that one day we will largely find cures for most genetic diseases. We will be making cell-based roads and buildings that easily last for hundreds of years. We will be designing microorganisms to break down plastics in the ocean and absorb greenhouse gasses from the atmosphere. We will make meat without killing animals, leather without cows, and have an abundance of food for next to nothing. We will eventually be able to program cells to do what we want. This is a future that I am obsessed with and I know is possible because I have seen the ingenuity of people first-hand.

Regardless of where life takes me, I am excited to work with amazing people every day on things that will make life a little bit better for all of us.